Offering: (Ho)ly Ontology x Zalika Ibaorimi

This article was originally published on August 15, 2021 on my Medium page.

This offering is my personal reflection regarding Zalika Ibaorimi’s teach-in (HO)LY Ontology: Black Visual Cultural Geographies of the Sexually Illicit.

Key term: Whorephobia (n): the fear or hatred of sex workers

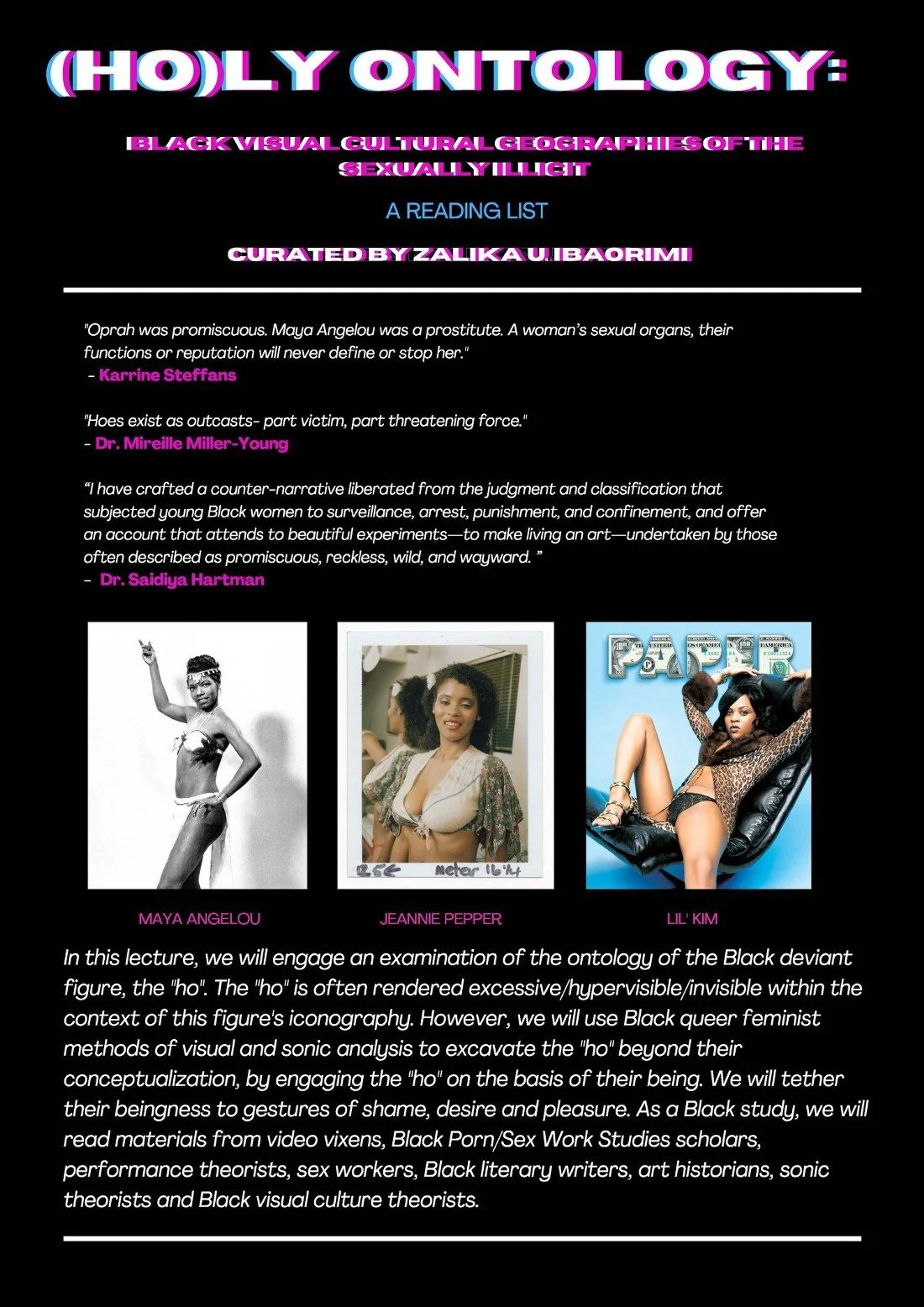

Philly native Zalika Ibaorimi is an afro-futurist, womanist, community organizer, multidisciplinary artist, Africana Studies scholar, and doctoral candidate at the University of Texas-Austin. Her research primarily focuses on “sexual shaming and deviant Blackness as a subset of Black Sexual Politics, through an Afrofuturist lens.” In a teach-in she gave for the School of Black Feminist Politics, through the platform Black Women Radicals, she offered an in-depth study of the “ho”. Ibaorimi engages with this Black deviant figure on the basis of their being rather than just merely unpacking the figure as a concept.

Ibaorimi covers a lot of theoretical ground with this teach-in. She leans on the work of scholars such as Dr. Mireille Miller-Young, Dr. Katherine McKittrick, Dr. Shawn Michelle Smith, Dr. Diana Taylor, and others. She analyzes how the Black female body has been rendered historically, the nuance of desirability politics, the criminalization of Black girls, shame, self-making, and much more. While Ibaorimi provided us a wealth of knowledge to sit with, I am particularly processing the throughline of respectability politics in combating negative stereotypes about Black women’s sexuality, the impact of erasure, and what Ibaorimi names “(dis)respectability through the logics of respectability.”

Ibaorimi posits that the “ho” is defined as:

A sex worker or erotic/sexual laborer. This can include prostitutes (or full-service sex workers), strippers, folks with OnlyFans, etc.

Those of us who engage in “non-normative” sexual decision-making practices. (I understand “non-normative” as anything that would be oppositional to the sexual purity and rape culture that we are socialized under.)

Black women that are “othered” through the logics of racialized science, medical sexism, and transphobia.

It’s important to note that “ho” is racialized, so not everyone that would fall under these categories are identified as hoes.

Historical Functions of Respectability Politics

To ground us, Ibaorimi offers a historical understanding of how the Black female body has been rendered. Countless Black feminist scholars have talked about how the legacy and violence of chattel slavery has impacted Black women. When thinking about early Black sexuality scholarship, much of the academic work around Black women’s sexuality was primarily focused on danger. In fact, Dr. Joan Morgan, in her article “Why We Get Off: Moving Towards a Black Feminist Politics of Pleasure”, has argued that this focus is another aspect of how chattel slavery continues to haunt us in the contemporary moment in how it hinders our ability to properly articulate pleasure in more holistic and nuanced ways. She speaks to how Black feminist scholars have done great work at spelling out the complex ways Black women’s sexuality has been hindered and compromised. Morgan (2015) goes on to say, “We’ve been considerably less successful, however, moving past that damage to claim pleasure and a healthy erotic as fundamental rights.” Ibaorimi articulates how because of this rendering of the Black female body, Black women are often read as whores as it is easy for any sort of content, even when not explicitly named as erotic/sexual, to be read as a function of their “illicit sexuality”.

This is similar to what I tried to discuss in a research project I presented in undergrad, titled “Jezebel, the Virgin: A Critique of the Sex Positive Feminist Movement”. I completed a literature review project that analyzed the intersections of the Jezebel archetype/caricature, the social construction of virginity, and the critical gaps within the mainstream sex-positive feminist movement. My research endeavor explained how historical tropes persist in the contemporary lives of Black women, including myself, and how that impacts our ability to embrace our sexualities in the most liberated of ways. With this understanding, it offers some level of compassion, grace, and nuance as to how and why respectability politics has been employed by a lot of Black women. However, it leads me to the question of what does it mean for Black women to engage in a liberated sexuality when those of us who are considered hoes are actively erased from Black history and black narratives and treated as outcasts within their community?

In speaking of erasure, Ibaorimi posits that ”sexually deviant Black women particularly sex workers” are outcasts and erased from the discourse of Black intra-communalism. While I haven’t studied Black history as extensively as I probably should, this notion makes perfect sense to me. We see this erasure often when Black history month comes around every February and we talk about some of the same Black cishet leaders while completely ignoring or covering up the fact that a lot of our bad bitch radicals were of trans experience, queer and/or hoes. (To be completely honest, I’ve been thinking about how perhaps the concept of being a “ho” is another iteration of queerness. Not a fully fleshed out thought but I think it’s worth interrogating.) To combat some of this erasure, some scholars have prioritized the nuanced narratives of hoes like Sadiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, Lashawn Harris’ Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners, and Ariane Cruz’s The Color of Kink. Even so, the threat of erasure of these Black deviant figures would probably be enough for a lot of Black women to embody respectability politics, and police other Black women through that logic, to avoid not being credited for their contributions.

Futhermore, respectability politics has served a variety of purposes for Black women historically. One of these purposes included protection. In 1989, Darlene Clark Hine introduced the concept “culture of dissemblance”, in the article “Rape and the Inner Lives of Black Women in the Middle West”, regarding Black women’s navigation in an oppressive environment. Culture of dissemblance refers to “the behavior and attitudes of Black women that created the appearance of openness and disclosure but actually shielded the truth of their inner lives and selves from their oppressors” and offers that this operated as a code of silence to combat attacks on black sexuality (1989). Dr. Cheryl D. Hicks, in her book Talk With You Like A Woman: African American Women, Justice, and Reform in New York, 1890–1935, discusses Black women’s adherence to respectability politics in conjunction with the criminal justice system in the Progressive Era and how being a respectable individual in the community had profound impacts on legal outcomes and sentencing practices (discussed in Chapter 4). Given this historical understanding, the work of dismantling Black women’s collective relationship to respectability politics requires extensive unlearning and healing. My own mom told me when I was younger that a woman can never really recover from the world knowing her ho shit and to me, that exhibits how deep sexual shame and respectability politics is for Black women.

The Emergence of (Dis)respectability Politics

What is more intriguing to me is the phenomenon Ibaorimi names as the “beautifying” or diluting of deviant performances in the name of respectability politics, or (dis)respectability through the logic of respectability. She offered an example, in the Q&A section of her presentation, of how we employ the phrase “ho phase” to express that this part of our life is dedicated to the pursuit of pleasure outside of the confines of “normative” sexual practices and that’s even rooted in respectability politics and sexual shame. I admittedly have participated in this way of thinking. For me, when I used to declare that I was in my “ho phase”, it functioned as a way to communicate that this moment in my life was dedicated to “sexual recklessness” and once I was done, I would be ready to commit to a relationship. Sounds raggedy but that was my mindset at the time. I’ve harbored some whorephobic ideologies and even while I’m actively trying to unpack and do better, I still have respectability politics in my back pocket when the perception of sexual deviance is too much for me to bear. I can remember how boys and men treated girls and women who were perceived to be hoes in music, movies, and even school. I can remember cringing at the thought of being perceived as sexually deviant. I distinctly remember a moment in high school when another student made the assumption that because I wasn’t sexually active in high school, I would be hypersexual in college. Leaning on respectability politics was much easier than calling out the blatant misogynoir and whorephobia especially while being raised in a sex negative environment. Shout out to my home state, North Carolina.

My experiences are more subtle compared to the more blatant expressions of the performance of (dis)respectability showcased when I see Black women artists, mainly rappers, utilizing the aesthetics of “ho” without standing ten toes down on their ho shit. Or they actively shit on sex workers while wearing their looks. Or they try to deny the influence of Black trans women specifically on the creation of the literal “ho” aesthetic (i.e. Amiyah Scott). It begs the question of what does it actually mean for Black women artists to cosplay ho shit while condemning actual hoes? What is the motivation for this commitment to whorephobia? How is the perpetuation of whorephobia connected to other forms of oppression? My first thought points to the role of capitalism in being able to “sell sex” in a fantasy without having the grapple with the reality of being a ho or properly paying the hoes for their influence. I also think about when hoes make it big in whatever industry they choose. In the case of Black women artists who have done ho shit to get to where they are in their careers, such as Cardi B, I think about the hierarchy of whorephobia or whorearchy. For example, Cardi B specifically used her stripper money to boost her rap career, which is fine. However, we must confront the contradiction of using their newfound access to more “respectable” ways of being, like marriage, to talk down on the hoes they used to be (i.e. “I don’t cook, I don’t clean/But let me you how I got this ring”). It’s worth interrogating how they resell the “cool” parts of the ho life without expressing the nuanced dangers of that positionality. It is easy to talk about the sex and the money. It is not as easy to talk about sexual shame, violence against hoes on interpersonal and institutional levels, and how we treat Black deviant figures on a larger scale. Of course, the onus is not solely on the artists; and the showrunners of the music/entertainment industry absolutely play a major role in these developments. Nonetheless, this phenomenon is worth pondering as consumers of music and entertainment. Even though I love amd enjoy the music that is being created by a lot of these women, this phenomenon does warrant pushback given its dangerous nature for non-sex workers and sex workers alike. Being marginalized in any capacity is not a safe space for anyone including the people that perpetuate the marginalization.

In conclusion, ho is life. Based on my observations thus far, I would argue that respectability politics is another carceral system that should be abolished like other carceral systems. Respectability politics disappears people and the ways that they contribute to our communities. It creates arbitrary and rigid good/bad girl binaries and reinforces separation from our peers. It also hinders our ability to fully embrace the authentic and complex expressions of who we are, not just Black women but Black people in general. It does nothing to shift the material conditions or misconceptions of Black deviant figures and it doesn’t even fully protect those who conform to those respectable scripts. If we’re committed to Black liberation we have to understand how harmful respectability politics is in freeing Black people. As Ibaorimi states, “let deviant things be deviant”, especially with the understanding that deviance is socially constructed along the backdrop of white supremacy, capitalism, patriarchy, and anti-blackness.

Reflection Questions (For Me and You)

What is the fear or the hindrance regarding the ownership of your sexuality? What would happen if you stood ten toes down on your ho shit?

Who does it benefit to perpetuate whorephobia? Who does it harm?

How does one unpack sexual shame in a way that doesn’t cause harm to others?

How does one organize for Black liberation in solidarity with the “ho”?