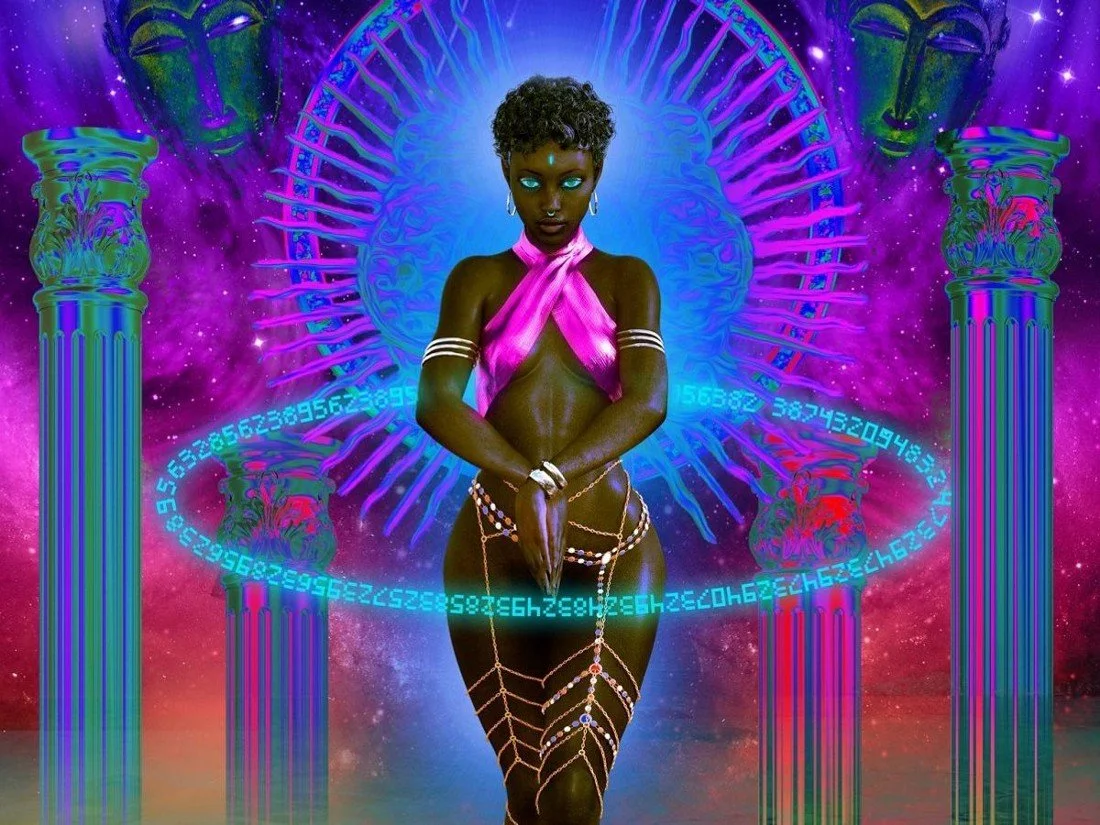

Afrofuturisticsolarpunkkink

I originally submitted this to Solarpunk magazine on September 14, 2022 for possible publication but after two months with no review I decided to withdraw my article and publish it on my Medium page. Enjoy!

I am Kahlia Phillips, a North Carolina native currently living life in the DMV area. I’ve been writing articles for the past two years, so I’m a baby writer of sorts. Admittedly, this is my first time engaging with the Solarpunk reimagination. Thus, I’m experimenting with what this framework can inform me about environmentalism and the imaginations around what is required of us, the humans, to be in better service to it. With this in mind, I utilize Solarpunk to analyze 3D printing, kink, and the environment. Taking it a step further, I also intend to include an Afrofuturistic and kink ecological perspective in this analysis. This piece will be in conversation with Madeleine Bavley’s “Getting Kinky With Ecology” and Rob Cameron’s two-part essay “In Search of Afro-Solarpunk.”

When researching some topics that I could analyze for this piece, I stumbled across this article that inspired me. The article talks about how the solarpunk movement could reconfigure how we navigate sex and sexuality. The author focuses on erotic technologies, which include but are not limited to, virtual reality, augmented reality, teledildonics, sex robots, and 3D printing of sex toys. They claim that 3D printing could reduce the need for the mass production of kinky tools in exchange for personally created and customized sex toys that could be recycled. As someone who has been on the receiving end of impact play with 3D-printed toys, I wanted to explore this concept more in-depth. 3D printing, also known as additive manufacturing, is the method of creating a 3D object layer-by-layer using a digitally created design. Kink is described as an array of non-normative[1] sexual and nonsexual practices, concepts, and fantasies that can also contain elements of BDSM (bondage/discipline, dominance/submission, & sadomasochism). Simply put, kink is a space for play and pleasure, like an adult playground or funhouse.

So what happens when you combine 3D printing and kink? Well, that would have to be at the discretion of your desires, needs, and creative energy. My only understanding of 3D printing and kink comes from one of my Black kinkster friends who has created toys for impact play and a suspension ring for rope bondage play. When I asked him what he enjoys most about creating 3D-printed toys, he stated that it is about being intentional and personal when designing for specific needs. He also likes to flex his design skills and kink expertise into each design. For example, if he wanted to create something that creates a sting sensation, he might design it so that the striking portion of the implement is either flat or in narrow strips. Plus, he would also design the handle in a way that allows for a firm grip on the toy. Pretty cool, right? Despite this impressive skill and making the list of plausible solarpunk-approved and sustainable erotic technologies, I believe that 3D printing, in general, and also in the specific context of sex and kink, caters more to the aesthetic of solarpunk rather than the foundational principles of solarpunk. I’ll explain more momentarily but first, let us consult some other folks.

Madeleine Bavley’s article, “Getting Kinky With Ecology,” critiques the limits of “doom and gloom” mainstream environmentalism. She considers how kink could provide perspectives for expanding environmentalism through critically analyzing pleasure and petroleum culture. Rob Cameron’s two-part essay series, “In Search of Afro-Solarpunk,” describes the basic components of Afrofuturism (“Part 1: Elements of Afrofuturism’’) and argues for the integration between Afrofuturism and Solarpunk (“Part 2: Social Justice is Survival Technology”). Bavley works, through her analysis, to suggest how we can also use the logic behind kink to address how destructive pleasure is on the planet and better imagine possible futures. The principles of consent, aftercare, and creative adaptability are foundational to the kink ecological approach. Cameron’s essay series grounds us in the notion that social justice is at the core of Afrofuturism and that we cannot properly address environmentalism without addressing systems of oppression. The collaboration of Afrofuturism and Solarpunk creates the potential for futures that place Black liberation at the center of our imaginations around pleasure and the planet. Both authors are adamant about suggesting alternative ways of thinking about environmentalism and such critiques give way to profound interrogations of our collective imagination for sustainable futures.

In returning to 3D printing and kink, when I asked my friend about the impacts of the 3D printing industry on the environment, he was transparent about how 3D printing materials are plastics that are not recyclable. Now, there are some redemptive qualities to some of these materials because some of them are used medically for prosthetics and bone replacements, are made to last, and can be food and/or body safe. For example, PLA is a plant-based filament and can decompose in 45–90 days. However, most materials and their waste are non-recyclable and have not reached a point where it is good for the environment. Recyclability is more or less an afterthought and the industry is more focused on doing less damage without costing more money in the name of product longevity. When I researched 3D printing I found that the filament, or slender angel hair-like fiber, for 3D printers is largely unregulated. Many filaments derive from overseas, some from reliable and upstanding companies, and some not so much. And while there are resins, or sticky flammable organic substances, that are rated body and contact safe and utilized in medical and dental industries, resins and thus resin printers are inaccessible for the average person.

Beyond the blatant environmental concerns regarding 3D printing materials, we have to think even broader about its implications. Earlier this year, Forbes published an article that stated that the 3D printing industry was valued at around $10.6 billion in revenue and expected to reach upwards of $50 billion by 2030. As an anti-capitalist, this is deeply concerning. With any industry, especially an industry with this level of value, there is infrastructure created to support it and we must be diligent in questioning the merit of 3D printing infrastructure. We have to think about the facilities that are built to house these operations. We have to think about the mining of these 3D printing materials. From a kink ecological perspective, aside from the fact that it satisfies the creative adaptability concept, which communities consented to the presence of these facilities? How was that negotiated, if it was? Was everyone involved fully informed about the impacts of 3D printing? Is there an opportunity for people to name that they no longer want the facilities in their communities? What processes are in place so that people can voice their concerns? In terms of aftercare, are there protocols in place to address any negative environmental impacts that may have occurred in the process? How are communities being supported? What is the proper way to navigate new technologies that can solve problems and create new ones? Still, we can go even further with these interrogations from an Afrofuturistic perspective. How are we addressing the possible levels of labor exploitation that are expected of a billion-dollar industry? If Afrofuturism can “connect with a living and usable past,” what were/are Afro-indigenous practices around kink that do not exploit the earth? How can we make use of what’s available in the terrain to create kinky tools? How are we engage in sustainable waste management without exporting to “developing” countries[2]?

All in all, I’m not expecting Solarpunk scholars to have concrete answers right now at this moment. We have to be willing to see beyond the frills and thrills of a solarpunk aesthetic if we are going to dream about what the fall of global racial capitalism could mean for the planet. Pleasure should not have to be at the expense of the planet. It also should not be viewed as a silly way to approach environmentalism. Skill building for pleasure is skill building for survival. Additionally, with anti-blackness being the organizing principle of the world, there needs to be more concentration on how dismantling systems of oppression, including environmental racism, is a huge part of truly sustainable solutions. We cannot afford to continue outsourcing our environmental suffering, we must holistically analyze it to combat it.

Additional Resources:

● https://edgeeffects.net/kink-ecology/

● https://www.tor.com/2019/10/29/in-search-of-afro-solarpunk-part-1-elements-of-afrofuturism/

[1] “Non-normative” within this definition is subjective and ever evolving as our societal notions of “normative” are ever evolving. What used to be considered kinky then might not have the same consideration in the present or future.

[2] About 88% of plastic waste in the US was exported to countries with loose and unregulated waste management standards in 2016.